Dog behaviour and learning: why do dogs behave the way they do?

Dogs are social animals and prefer to be part of a group. When it comes to pet dogs, the family – which might include one or more people as well as other pets – is their group.

Despite what was previously believed, from a scientific perspective dogs do not qualify as pack animals. The term ‘pack’ suggests there has to be a leader who exerts dominance over other members of the pack. They are in fact social animals, and as such ‘dominance theory’ is irrelevant.

It was adjunct Professor David Mech who first coined the term ‘alpha’ wolf that was used in his book that was published in the 1960s. He has since revoked this term, and explains that it has been incorrectly used to describe relationships between domestic dogs.

Mech states (2010): “Rather than viewing a wolf pack as a group of animals organized with a ‘top dog’ that fought its way to the top, or male-female pair of such aggressive wolves, science has come to understand that most wolf packs are merely family groups formed exactly the same way as human families are formed.”

‘Dominance theory’, as described by Schenkel (1946) in his observations of captive wolves has been found to be flawed as it is based on invalid science. So, the need to dominate your dog through forceful control is unnecessary. In fact, it can have a significant negative impact on your dog’s behaviour and your relationship with your dog.

The myth of “undesirable dog behaviour”

When your dog exhibits what is natural dog behaviour, you may sometimes see it as inappropriate. Barking, digging, mouthing, chewing, jumping up, pulling, growling, or even biting are all natural behaviours. Left unaddressed, such behaviours can lead to unhappy and frustrated dogs and owners.

Dogs don’t understand ‘good’ and ‘bad’ behaviours. They understand ‘safe’ and ‘not safe’ behaviours. For example, your dog will not consider it safe to urinate on the floor in front of you because your body language indicates that something is wrong. However, if they urinate on the floor behind the couch, this will be ‘safe’ behaviour in your dog’s mind.

They are not being ‘bad’ or ‘sneaky’ or ‘dominant’, they are being ‘safe’. Your dog isn’t being ‘naughty’ – they are just being a dog who has yet to be guided by you as to what they should do in every circumstance.

Communicating with your dog

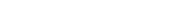

We will never know exactly how a dog feels about things. But we can try to understand something of what dog’s feels by learning to read their body language.

This is a dog’s main form of communication, and we can greatly improve out interactions with dogs by spending time trying to understand their body language.

It is difficult to interpret what the whole body of the dog is telling us. The best way to begin is by observing various parts of the body for specific signs and then consider them all together.

We all know that a tail tucked between a dog’s legs usually means a frightened dog. However, we are misinformed if we believe that a wagging tail is always a ‘happy’ tail. It can also indicate arousal or aggression depending on the tail position and motion and other signs.

How we interpret the movement or non-movement of each body part will give us a greater understanding of what our dogs are telling us.

Again, most people know that if a dog’s ears are flat against their head then they are not comfortable or happy. However, there are many different ear positions that, in conjunction with the tail position and movement, will tell you how your dog is feeling.

Staring directly into a dog’s eyes can be threatening. Brief eye contact is fine but staring is to be avoided. When a dog shows the whites of their eyes (known as ‘whale’ eye) they may be aroused or frightened and ‘asking’ for space.

When you have learnt to interpret all of the different body parts individually, you can start to combine them. The overall picture of the dog will reveal a great deal about how they are feeling. This will make life better for both you and your dog.

Want to know more?

- The Dog Decoder App teaches you how to read your dog – and also what all dogs are trying so hard to tell you.

- The Pet Professional Guild has excellent advice regarding how to read dog body language.

- This ‘body language of fear’ poster is hugely informative.

How dogs learn – it’s all about doing what feels good

Dogs do what feels good and what works for them. When training your dog you can use this to your advantage by making a positive association with the behaviours you want, and ignoring or redirecting the undesirable behaviours.

By managing the training environment, ignoring or redirecting inappropriate behaviour, and rewarding wanted behaviour, dogs will learn quickly.

Using positive reinforcement consistently is effective because learning is strengthened through repetition – as described by the Australian Veterinary Association in their information sheet, Reward-based training.

Many decades ago the majority of dog trainers relied upon force and correction as the sole method of training. Some trainers today still use methods based on the concept of ‘dominance’ and having to be a ‘pack leader’.

However, such theories have been discredited, and the associated training methods are viewed as aversive by many progressive dog trainers and professional organisations.

When an animal continuously experiences something unpleasant, some will become unable or unwilling to avoid further negative experiences, which is often displayed as no response.

When dogs are frightened and confused as to what is required of them, they may stop trying and shut down completely in order to avoid further unpleasant consequences. This is known as ‘learned helplessness’ (Lindsay SR 2000).

Your dog is never trying to dominate you, research shows

The Australian Veterinary Association states in their ‘Debunking Dominance in Dogs’ information sheet: “If your dog is growling, baring its teeth or snapping at you or others, it is not because they’re trying to dominate you. Often anxiety and insecurity are the primary contributors to aggressive behaviour. Dogs with medical conditions or those in pain are also more likely to be irritable or react defensively.”

Some trainers mistakenly refer to this lack of response as the dog being calm and/or submissive. However, in many cases, the dog has given up due to confusion and fear.

A 2014 study published in the Journal of Veterinary Behaviour found that dogs trained using aversive techniques are far more likely to show signs of stress than those trained using positive methods. The research involved monitoring two dog training schools. One used corrections where dogs were trained using force, such as having their collar jerked. At the other school the dogs were rewarded when they performed the desired behaviour.

The findings in the study suggest training methods based on positive reinforcement are less stressful and better for the dog’s welfare (Deldalle & Gaunt 2014).

Many people feel uncomfortable using force or other aversive techniques when training their dog but are not aware that alternative non-aversive methods are available. Force-free training is now being offered more widely and people are choosing to leave clubs or schools, where they or their dog are not comfortable, to enrol in force-free training.

The best dog training methods

Dog training in South Australia is currently unregulated. This means that anyone can declare themselves a dog trainer without any formal qualifications or experience. RSPCA South Australia would like to see dog training regulated and is working with the relevant authorities to help make this happen.

Many trainers use either correction-based methods or ‘balanced’ (reward and correction based) methods. As more dog guardians request force-free training, more trainers will offer their own versions of this type of training. Care must be taken to ensure the trainer truly understands the theory behind the practice of force-free training and this takes a lot of study and hands-on practice.

In this section you will find information on how to choose a dog trainer. We also encourage you to visit our force-free trainers list.

Why we recommend force-free dog training

The basis of force-free training is to focus on what you want your dog to do, and rewarding desired behaviours. Force-free training does not involve force, corrections, or the assertion of dominance over your dog.

Force-free training – also known as positive reinforcement or reward-based training – is the preferred training method used and promoted by many organisations and professional bodies around the world, including RSPCA Australia, The Australian Veterinary Association, The Pet Professional Guild, The Humane Society of the United States and the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior.

RSPCA recommends these training methods as the most humane and effective way to train dogs, as it is enjoyable for you and your dog and positively enhances the bond of mutual trust and respect. The key principle of force-free training is ‘first, do no harm’.

If an undesirable behaviour occurs, rather than correct or punish, it is essential to consider the underlying cause of the behaviour. For example, a dog that jumps up may be seeking attention or giving a social greeting. Once the motivation is identified, you can then teach your dog an alternate behaviour – ‘sit’ for example. Then, when you think your dog may jump on you, you ask for a ‘sit’ before the dog jumps and reward the ‘sit’, reinforcing the behaviour of sitting. Sitting will then become the automatic behaviour.

Rewards can be given in the form of a small food treat, play with a toy, verbal praise or petting – preferably not on the head, as this makes most dogs uncomfortable. By rewarding preferred behaviour you are reinforcing it, and this greatly increases the likelihood that your dog will do it again.

Want to know more about force-free training? Sign up for our FREE 6-part video course

To help show you how simple and fun force-free training techniques are, our RSPCA South Australia dog trainer Heather Bradley has created a free and easy-to-follow 6-part dog training series. She’ll show you how to teach your puppy or dog to sit, drop, touch, walk on a loose lead, come, wait and other super cool tricks.

Watch Lesson 1 below, then simply pop your details in the form to receive the next 5 training videos straight to your inbox – absolutely free of charge. We hope you find the videos and tips useful and have lots of fun training and bonding with your dog.

You can also see this video on recall progression and this video on effective control to learn more about how to positively train for good doggy etiquette at the beach.

Get instant access to our free dog training course

What’s wrong with ‘dominance’ model training

Many major animal welfare, training and veterinary organisations strongly advocate against dominance training – for good reason.

RSPCA Australia states: “The ‘dominance’ model for dog behaviour poses serious dog welfare problems. RSPCA’s position is that dogs should be trained using programs that are designed to facilitate the development and maintenance of acceptable behaviours using natural instincts and positive reinforcement. Aversion therapy and physical punishment procedures must not be used in training programs because of the potential for cruelty. Punishing a dog for ‘unwanted’ behaviour can actually exacerbate the problem.”

The Association of Professional Dog Trainers states that “physical or psychological intimidation hinders effective training and damages the relationship between humans and dogs”.

The American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB) notes that punishment can cause several adverse effects, including “inhibition of learning, increased fear-related and aggressive behaviors, and injury to animals and people interacting with animals”.

The Australian Veterinary Association states in their Debunking Dominance in Dogs information sheet: “Anyone with a ‘pushy’, ‘rude’ or ‘demanding’ dog has probably been told at some stage to ‘show them who’s boss’ or to ‘make them submit’. The advice usually involves physically punishing the dog by forcing it onto its side (the ‘alpha roll’), or to hold eye contact whilst growling at the dog. These confrontational techniques are a bad idea. They are very risky and may result in escalation of aggression. Punishment will not calm an agitated dog. Punishment will increase both fear and excitability, and a growl may then escalate into a bite. Punishing your dog for growling may also inadvertently teach it to suppress the warning growl and bite with no warning. If your dog is anxious, punishment will make the anxiety worse. Punishment also fails to teach your dog how you want it to behave, and can ruin your dog’s trust in you and other people.”

A 2009 University of Pennsylvania veterinary study found most dogs with owners who use aversive methods to train aggressive pets will continue to be aggressive unless training techniques are modified. This study also showed that using non-aversive (force-free) “or neutral training methods such as additional exercise or rewards elicited very few aggressive responses”.

Just got a puppy? Sign up for puppy pre-school!

We highly recommend booking your puppy into puppy pre-school classes, which are an important way of socialising your puppy with other dogs.

Puppies have a ‘critical socialisation period’ from approximately 3 to 16 weeks of age. This is the time when they need to socialise with other dogs in order to learn social cues and how to communicate appropriately.

Find a puppy pre-school class which permits pups to attend prior to completion of their full vaccination regime (i.e. have had only their first or second vaccination), because waiting until the final vaccine is given will result in missing the ‘socialisation’ window of opportunity. Precautions can be taken to minimise disease risk before the vaccination course is completed.

Have an adolescent, adult or senior dog?

If you have an adolescent, adult or senior dog, we recommended attending force-free dog training classes with them. Many force-free trainers offer in-home consultations for dogs that may find classes too stressful.

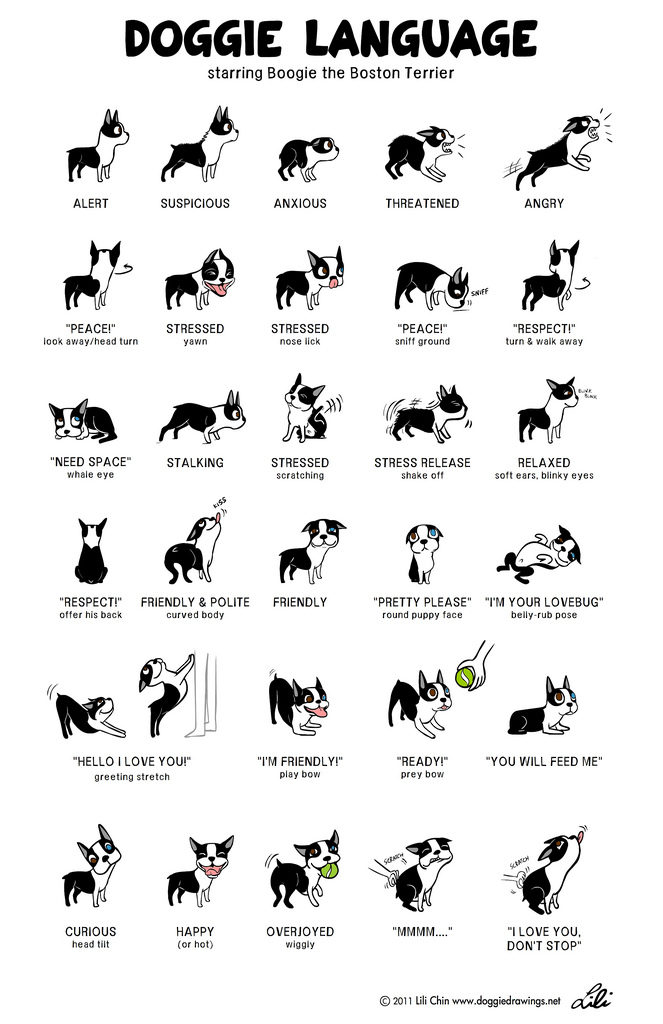

Be aware of the Yellow Dog Project

The Yellow Dog Project encourages guardians to use a yellow lead, ribbon, vest, and/or bandana to communicate that their dog needs some space and to not approach them with your dog.

The yellow items also signal to other guardians with dogs to keep at a distance and to allow time for the ‘yellow dog’ and their guardian to move away.

The dog walking equipment RSPCA recommends

We recommend walking harnesses for dogs, which can help manage and prevent pulling on the lead – but should be used in conjunction with force-free training. See our detailed blog on which harness to use when.

Front-attach harnesses

A front-attach harness is our first choice for recommended equipment when training and walking your dog, as it offers good control while being humane and gentle. The harness goes around your dog’s midsection behind the front legs, and loops around the chest with a leash ring at the front. A dog’s centre of gravity is located at the chest, so when they pull, the harness is designed to gently turn the dog toward you which helps to stop pulling on the lead. There is no pressure or restriction on the neck and dogs accept the front attach harness easily. But it's essential to ensure that the harness is fitted correctly.

Back-attach harnesses

Back-attach harnesses are the most common type used, especially with small dogs. However, they are often ineffective in preventing pulling, as your dog can use their full body weight to pull on the lead. If your dog doesn’t pull then the back attach harness is a safer option than a collar. If your dog does pull then it is best to use a front-attach harness.

Leads

Legally, in South Australia, your dog must be on a lead no longer than two metres in length at all times in public places, under the Dog and Cat Management Act 1985 – unless in a designated off-lead park or beach where they need to be "under effective control". We recommend walking your dog on a lead made of cotton webbing or similar material up to two metres in length – in conjunction with a harness, rather than just a collar.

Double-ended leads

Double-ended leads have two points of contact with a clip on each end and rings at varying intervals along the lead. The double-ended lead can be used with a front-attach harness; one end of the lead attaches to the front ring at the chest and one clip attaches the ring on the back. Using a double-ended lead can help when training your dog to walk on lead as it gives more control with two points of contact. The rings attached along the lead also means it can be used as a normal lead by attaching one of the end clips to the dog's harness and then looping the other end over and attaching it to one of the rings on the lead creating a loop at the end to hold on to. Double-ended leads are generally used under the guidance of a force-free trainer. It is not recommended to use one without professional advice.

Illegal and non-recommended equipment that should be avoided completely

Some collars cause pain or distress upon your dog, which always leads to a reduction in the quality of the relationship you share with your dog. Dr Susan Friedman likens it to a bank account. The good times you spend with your dog builds a strong bank balance of mutual trust and respect. If you physically correct or intimidate your dog then you have made a large withdrawal from that account.

The use of collars that constrict the neck, such as check or prong collars, also have a high risk of causing damage to sensitive tissues such as the trachea (windpipe), the oesophagus (food pipe) and thyroid glands.

You may think that a dog will not pull if it causes pain. However, the urge to pull can be stronger than the aversion to pain, resulting in significant tissue damage in the neck region. In addition, even though the pulling or ‘checking’ (correction) is done intermittently, its effect is cumulative and contributes to repetitive trauma of the neck.

Check collars

Check collars are primarily made of metal chain and are designed to tighten around a dog’s neck whenever pressure is applied. These collars slip over a dog’s head and attach to the lead. They are promoted by trainers to correct unwanted behaviours by jerking on the lead to cause a rapid constriction around the neck. The American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior warns of the inherent dangers of using check collars including causing or increasing aggression, potential to increase undesired behaviours and physical damage to soft tissue structures in the neck.

Prong collars

Prong collars (also known as a pinch or constriction collars) are also made of metal and are designed to tighten around a dog’s neck whenever pressure is applied. The prong collar has a series of fang-shaped metal links, or prongs, with blunted points which when pulled pinch a dog’s neck. These collars are used to correct unwanted behaviour. Even if used without corrections, these collars can still cause pain, discomfort and injury to your dog and, in extreme cases, brain damage (Grohmann et el 2014). Under Australian Customs legislation, it is illegal to import ‘pronged collars’. However, many dog owners are not aware of this and unscrupulous distributors import the collar in segments to avoid breaching the import legislation. Upon arrival, the collars are reassembled and sold. In April 2014, a petition on Facebook succeeded in pressuring Amazon UK to stop the sale of prong collars. After receiving the petition, the online retailer stopped selling the aversive dog collars on their website. RSPCA South Australia will continue to investigate ways to stop the import, sale and use of prong collars.

Other non-recommended collars

Some products on the market are aimed at preventing dogs from barking or engaging in other unwanted behaviour, such as escaping. These products include electric shock collars (collars that deliver an electric shock to your dog), sound collars (collars that emit a high-pitched sound) and citronella collars (collars that spray your dog’s face with citronella scent when it barks).

RSPCA Australia does not recommend the use of these specific collars to stop your dog barking for a number of reasons:

- They’re often ineffective as some dogs do not associate the punishment (e.g. shock or citronella spray) with the behaviour.

- They tend not to be successful because they fail to address the underlying cause of the behaviour (e.g. play, fear etc) and may only temporarily mask the problem or some dogs may habituate to the collar and barking will resume.

- Sometimes it is appropriate for dogs to bark (e.g. as a means of communication) in which case the collar punishes them for normal behaviour. There is also the potential for abuse if the collar is routinely left on for too long.

The treatment of undesirable behaviour such as excessive barking should begin by consulting with a force-free trainer, who can help identify and address the cause of the problem.

Illegal – electric shock collars

It is illegal to use electric collars (even if not switched on) of any type in South Australia under the Animal Welfare Act. People who place an electric collar on their dog risk a $10,000 fine or 12 months' imprisonment. If you know of anyone recommending or using one of these collars, please call our 24-hour cruelty hotline on 1300 4 777 22.

Citronella collars

Dogs have a highly developed sense of smell and the strong odour emitted by citronella collars is very unpleasant and aversive. Citronella collars are used as a ‘quick fix’ but fail to address the underlying cause of the behaviour and therefore have limited success. They may also create unwanted side effects.

High-pitched sound collars

Dogs have very acute hearing and ultrasonic dog collars deliver a high frequency sound. No evidence is available to confirm that these are not harmful, so RSPCA does not recommend the use of these devices. Reports have been received where dogs have shown very fearful, anxious or distressed behaviour due to these high pitched sounds, including both the ‘target’ dog and any dogs in the vicinity such as neighbouring dogs.

Flat collars

Flat collars are commonly used to hold identification and registration tags, which is acceptable. However, these collars should not be used for dog walking. If your dog pulls on the lead while walking, the pressure on the neck and throat can cause discomfort and possibly injury. By using a front attaching harness and force-free training instead, loose lead walking can be achieved very quickly.

Martingale collars

Martingale collars are similar to flat collars but tighten when the dog pulls. As with flat collars, it is not recommended to use a martingale collar if your dog pulls on lead as damage can still occur. Use a front-attaching harness and force-free training instead.

Flexi or retractable leads

These are not recommended as they have caused serious eye and hand injuries (including burns, cuts and amputations) to handlers, and also pose a very serious risk to children who may use them. Injuries have also been caused to dogs. These leads do not allow effective control, often break, can cause tangles and also encourage your dog to pull, as they learn that pulling extends the lead. They often extend longer than 2 metres and are therefore not legal.

Head collars

Also known as head halter, head collars are designed to help manage your dog by guiding the head, just as halters are used with horses. A head collar is not recommended as the first option for walking, as many dogs find them uncomfortable and dogs need to be given time to adapt to wearing one. Ideally, head collars should only be used under the advice of a force-free trainer or a qualified veterinary behaviourist.

Ready to find a force-free trainer?

Hopefully you now understand that finding a good force-free dog trainer is essential for you and your dog’s welfare, and can make a positive difference in both of your lives.

When researching and choosing a dog trainer, be sure to emphasise that you wish to only use force-free methods and that you do not support the use of check chains, prong collars or any methods that may cause discomfort or distress to your dog.

Do your research before engaging a trainer

Most trainers on our force-free trainers list offer in-home consultations, which might be more suitable for you and your dog. In-home consultations are a convenient option as each session can be tailored to your specific needs.

We have also provided some questions for you to ask when making enquiries with dog trainers.

When researching dog training classes, we suggest you ask to personally attend and observe a class, without taking your dog, prior to enrolling. This allows you to see the class for yourself, meet and observe the trainer, speak to other dog owners about their experiences and see what training methods and equipment are being used.

Once you do start a class, if you have any doubts or feel uncomfortable with any methods being used you have the right to speak up and to leave the class at any time.

Our RSPCA Dog Training school is completely force-free and offers classes for puppies and dogs of all ages and sizes.

Questions to ask when speaking to a dog trainer

Q. Are you on the RSPCA South Australia’s force-free trainers list?

To save you time, we recommend you contact a trainer included on the list. However, if there isn’t a force-free trainer near you, continue asking the following questions.

Q. Where did you learn how to work with dogs?

Formal training and hands on experience under the supervision of a force-free professional is key.

Q. What kind of training equipment do you recommend?

Soft collars, front-attach harnesses and head collars only for reactive dogs.

Q. Do you use check collars and/or prong collars?

Avoid trainers who use and recommend check collars and/or prong collars.

Q. Do you use force-free training methods ONLY?

Look for trainers who use force-free training methods only.

Q. Do you use corrective methods?

Avoid trainers who use corrective methods.

Q. How many dogs are allowed in your classes?

Best practice is 8 dogs per instructor with an assistant or 6 dogs for an instructor on their own.